Most people are now familiar with concussion risks and football, thanks in large part to awareness stemming from Washington’s first-in-the-nation legislation (The Zackery Lystedt Law[1]) aimed at preventing preventable brain injuries, as well as national media attention on NFL players and the long-term effects of brain injuries. However, when it comes to youth athletes, there is less familiarity in the community about such risks and the reality of young female athletes and concussions from sports. Several recent studies released in 2017 help to further illustrate that when it comes to concussions (a type of traumatic brain injury), there can be considerable differences between young male and female athletes. These differences can range from how likely young women might be to report a concussion, to the differences in how young women recover from a concussion, and whether young women might be at greater risk than young men by being allowed to return to play too soon after a concussion. The central theme shared by all of the studies is clear: young female athletes should not necessarily be grouped in with their football-playing young male counterparts when it comes to the evaluation, diagnosis, and treatment of sports-related concussions.

I. Girls’ Soccer Can Lead to More Frequent Concussions Than Other Sports

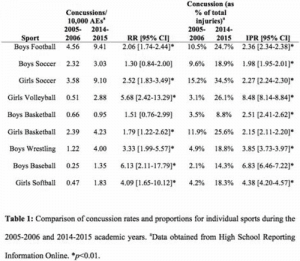

A July 2017 study published in the Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine addressed findings from a 10-year study of young athletes between years 2005–2015.[2] The purpose of the study, in part, was to help identify whether a particular sport predisposed an athlete to a greater risk for concussions. Athletic trainers from U.S. high schools provided a majority of the information gathered in the study. The findings from 2014 – 2015 revealed that young athletes were most likely to have sustained a concussion if they participated in girls’ soccer. In fact, girls’ soccer resulted in a higher rate of concussions than girls’ volleyball or girls’ basketball. Overall, young female athletes participating in girls’ soccer, volleyball, and basketball all had higher concussion rates than young male athletes participating in boys’ football. (Table 1). The study also tended to indicate that the higher incidence of concussion among young female athletes might be partially attributed to girls being more likely and willing to report symptoms when they appear.

II. First-Time Concussions In Girl Athletes: Rates of Recovery are Different than Males

A 2017 study published in the Journal of the American Osteopathic Association addressed whether female athletes in middle school and high school who suffered their first sports-related concussion were symptomatic for longer periods of time than their male counterparts.[3] This has continued to be a topic of discussion since the Fifth International Conference on Concussions in Sport, held in 2016, in which researchers concluded there was some evidence that girls could be at higher risk than boys for concussion during their teenage years.[4]

The results of the 2017 study of 212 athletes concluded that female youth athletes aged 11 to 18 years with first-time, sports-related concussions were symptomatic for longer compared to male athletes of similar age. There was no single explanation for the difference, and the researchers acknowledged that the causes were complex, multifactorial in nature, and depended on the individual patient’s situation. However, the researchers did address the biological differences between the sexes, including the differences in neck sizes, head mass, and other studies that suggest female brains may need to metabolize more glucose after a concussion, making the recovery take longer.[5]

III. Young Female Soccer Players are Five Times More Likely than Young Males to Return to Play the Same Day Following a Concussion

At the 2017 American Academy of Pediatrics National Conference and Exhibition, researchers from a pediatric sports medicine clinic in Texas presented a study abstract involving the return to play of young female soccer players after a concussion.[6] The study examined young soccer players of both genders in the 14-year age range who had been diagnosed with a concussion while playing. Of the 87 athletes diagnosed with a concussion related to playing soccer, two-thirds (66.7%) were female. Surprisingly, over half of the girls diagnosed with a concussion were back on the soccer field playing in a game or practice on the same day as their concussion. By contrast, only 17.2% of boys were back on the soccer field the same day.

The researchers expressed concern over these study findings, citing previous studies that showed girls suffering twice as many concussions as boys. The researchers expressed additional concern with this quick return to play given the recommendations of numerous medical organizations, including the American Academy of Pediatrics, and laws in all 50 states to protect the developing brains of young athletes.

IV. Conclusions

Youth female soccer players are as likely to sustain a concussion as young male football players, if not more so. These young women may be more likely to tell someone that they are experiencing what they believe to be the effects of a concussion, but, they may also be more likely to want to return to play as quickly as possible so as not to let down their families, their teammates, or themselves. Laws created to protect student athletes, such as the Zackery Lystedt Law[7], help protect against the dangers of concussed athletes of every kind from being allowed to return to play too soon. It is important to recognize the high risk of concussion associated with girls’ soccer, cheerleading, lacrosse, basketball, and volleyball, among other sports. Greater understanding will help reduce preventable brain injuries, and help shape appropriate care after a brain injury.

[1]The Legal Landscape of Concussion: Implications for Sports Medicine Providers. Andrew W. Albano, Jr., DO, Carlin Senter, MD, Richard H. Adler, JD, Stanley A. Herring, MD, Irfan M. Asif, MD. Sports Health, Vol 8, Issue 5, pp. 465-468. August 16, 2016.

[2] Assessing Trends In the Epidemiology of Concussions Among High School Athletes. Michael S. Schallmo, BS1, Joseph Arnold Weiner2, Wellington Hsu, MD3. The Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine, 5(7)(suppl 6)

DOI: 10.1177/2325967117S00439

[3] First Time Sports-Related Concussion Recovery: The Role of Sex, Age, and Sport. John M. Neidecker, DO, ATC; David B. Gealt, DO; John R. Luksch, DO; Martin D. Weaver, MD. The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association, October 2017, Vol. 117, 635-642. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2017.120

[4] McCory P, Meeuwisse WH, Dvorak J, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 5th international conference on concussion in sport held in Berlin, October 2016. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51(11):838-847. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2017-097699

[5] Anderson PJ, Zametkin AJ, Guo AC, Baldwin P, Cohen RM. Gender-related differences in regional cerebral glucose metabolism in normal volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 1994;51(2):175-183.

[6] https://www.aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/Pages/Female-Youth-Soccer-Players-Five-Times-More-Likely-than-Boys-to-Return-to-Play.aspx

[7] http://apps.leg.wa.gov/RCW/default.aspx?cite=28A.600.190